**Dedication**

This story is dedicated to:

My Great God and Jesus Christ, the Rock I stand on, in Whom I live, move,

and have my being, and to tell all the wonderful loving people He has sent

to help us during and after David's accident, who are the body of Christ, His

church. This book is a thankful tribute to the faithfulness of God, and to each

person who has helped Dave become a functional human being once again.

~Leone Nunley

The article shown below appeared in the Yakima Herald Republic in April of 2006. Our thanks go to writer Jane Gargas.

For every setback, Nunley also portrays a savior, whether it's an understanding physician - local doctors Roger Bracchi, Majorie Henderson and Sean Mullin are singled out- legions of sympathetic fellow parishoners from West Side Baptist Church, such as Kathy and Larry Perrigo - caring neighbors, Floyd and Cheryle Strauss, or a supportive husband, Dale Nunley, David's stepfather.

It's been a grueling long haul; nothing has come easily to the family or to David, now 43 years old. In essence, he had to learn his infancy again, everything from swallowing and crawling to toilet training and lifting a glass. "David is still making physical and mental strides," Leone Nunley explains before the recent filming session. "There are small gains, like learning new words. He says 'golf' when we drive by the golf course and 'doctor' when we go by the hospital."

Through years of physical therapy, David has conquered many barriers: eager and sweet-natured, he communicates through hand signals and words and by loudly vocalizing his approval when pleased - and that's almost all the time.

His signature gestures are a beaming smile, a quick squeal and a thumbs-up motion.

"He is such a happy person," notes family friend Jacquie Wonner.

After living at home for 12 years, David moved to a duplex in southwest Yakima several years ago with a full-time caretaker, Adelina Cuevas.

Together, David and Cadousteau work on weightlifting and stretching exercises to keep David in shape when he's not using his walker or his wheelchair.

They also do enrichment activities, like spelling. David can write his name and has a fairly large passive vocabulary. "He understands more than he says," notes Cadousteau.

He certainly understands what he likes: chocolate ice cream, UNO, Miner's Drive In, organ music in church, Star Trek.

As Nunley notes in the booik, not every person who sustains a brain injury will recoup even a small vestige of life. But she underscores that it was important for her to try everything she could.

"When, from a human perspective, you find yourself looking at a child who is now only one-third of what he or she used to be, you can throw up your hands and run - or you can get to work with the one-third that's left. Every time the person makes the tiniest step of progress, it is a precious moment," Nunley writes.

She theorizes that the main difference in Terri Schiavo's and her son's outcomes was not the highly visible family battle over the feeding tube. Instead, she thinks that the die was cast years earlier when Schaivo didn't receive the kind of stimulation and vigorous therapy that David did.

Nunley acknowledges the difficult decisions that surround these cases, not the least of which are the medical and ethical issues of prolonging life.

With some 1.4 million American sustaining traumatic brain injuries every year, the path each family must take, measuring the quality of life, in many cases is not clear-cut, she admits. There's a delicate balance.

Not surprisingly, David's accident 17 years ago has had a profound effect on family members.

His younger brother, Bill McRae, works as a registered nurse in the neurosurgery department at Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital. He chose that field, he says, because of his experiences with his brother after the accident.

"I'd like to think I've carried on that caring tradition," he says.

But others, such as neighbors, church members and friends, also testify to how much how David's life has touched theirs.

Which brings us to David's crowded duplex last month.

More than a dozen friends gathered to tell their roles in David's story for the film crew from Atlanta.

These were the people who consoled the Nunleys through the harrowing, early days, later read books to David and played Connect Four with him, then took turns helping with a massage therapy called Patterning, with the hope of stimulating muscles into regained use.

Before the filming session began, Brian Connor, senior producer for In Touch Ministries, explained to the gathering that the Christian organization is planning to cover the account of David's fight for life with television and radio broadcasts and in their magazine.

Although no dates have been set, Connor said the crew is aiming for all three segments to run in July; the ministry's Web site will have details.

Locally, the television show is carried on several outlets, including the Trinity Broadcasting Network at 5 p.m. Saturdays. The radio show plays locally on several stations every day.

With camera rolling, the assembled group talked about what it was like first hearing about David's accident.

"Painful" and "devastating," remembered friends Gene and Erma Kimmel.

The news deflated Joy Campbell. "I had that sinking feeling that this was in the medically impossible range."

"But," she added, "we had the Lord."

Bill Campbell and Millie Johnson described the patterning therapy, which began in 1991, as giving them a sense of hope.

When David made progress, Dorothy Dyer called it a "wonderful demonstration of God's love."

Two women drove from out of town to tell their pieces of the story. One was Linda sharp from Spokane, the person who happened on the accident scene and held David's hand before the ambulance came.

"It's a miracle he's here; he was so far gone ... but his Mom wouldn't take no for an answer," Sharp said.

Cara Anderson traveled to the filming session from Vancouver, Wash.; a nurse, Anderson was working at St. Elizabeth's Hospital (now Yakima Regional Medical and Cardiac Center) when David arrived there 17 years ago, unresponsive and showing little hope of recovery.

"I recognized that there was a soul in there, that David was in there," Anderson said.

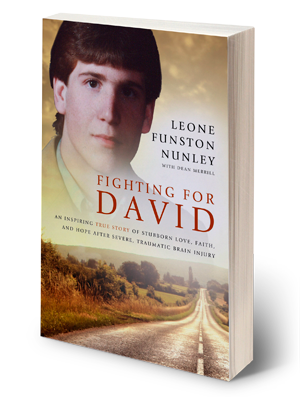

And it's that soul that his mother has chronicled in "Fighting for David."